Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor and thymoma: unusual presentation for two types of rare tumors: a case report

Introduction

In 2002, Ishikawa described in the Japanese literature, a peripheral lung nodule with an unusual architecture consisting of ciliated columnar epithelial cells combined with goblet cells and a basal cell proliferation that he named “ciliated muconodular papillary tumor” (CMPT) (1,2). Now it is considered as bronchiolar adenoma (3,4). We report the case of a female patient with a CMPT and a mediastinal mass diagnosed as B2 thymoma.

This is the first case of CMPT in Latin America. In a recent literature review of 41 published cases (5), most of these tumors were seen in Asian elderly patients, with an exemption of one 19 years old patient (6), so it should also be considered as differential diagnosis in a broader age group. We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med-20-60).

Case presentation

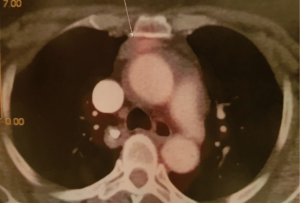

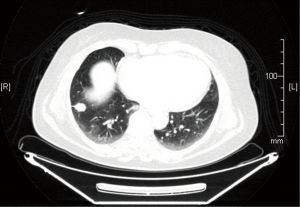

A 68-year-old woman with a 40 pack-year history of smoking was referred to our hospital. No other medical past history was recorded. The chest radiograph showed a nodule with irregular borders in right lower lobe (RLL) which was confirmed with a chest computed tomography (CT) which led to suppose in the first instance a pulmonary malignant process. The fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan of the whole body confirmed a 20 mm mass with an irregular contour irradiating towards the visceral pleura and small central cavitation and moderate uptake [standardized uptake value (SUV) =2.7]. In the anterior mediastinum there was a solid 25 mm nodule with an SUV of 2.4, interpreted in the CT as well as in the PET scan, as a pre-vascular lymph node enlargement (Figures 1,2). Due to the central location of the lesion, it was not technically possible to perform a transthoracic biopsy.

During video-thoracoscopic surgery, intraoperative FNA of lung injury was performed and the presence of malignancy was reported, without tumor typing, which led to RLL lobectomy. In the anterior mediastinum there was a mass closely related to the thymus that was resected by video thoracoscopic approach; no intraoperative diagnosis was made. Lymph nodes R4, 7 and 10 were negative.

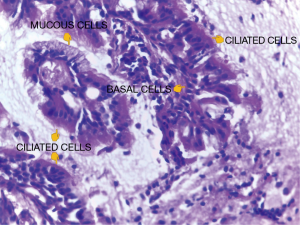

The gross examination of the RLL revealed a solid nodule with some cystic areas and irregular borders, measuring 1.8 cm in its largest dimension. Microscopy showed a focal area of irregular fibrosis and a papillary neoplasm with ciliated columnar epithelial cells, mucin-producing cells, basal cells, mucus lakes within the alveoli and absence of necrosis and nuclear atypia (Figure 3). The proliferation had a growth pattern following the alveolar septa in the peripheral areas. Final diagnosis for this lesion was CMPT.

The lesion located in the anterior mediastinum, was a brownish and nodular fragment measuring 2.5 cm in diameter. Upon microscopic examination it showed thymic tissue and a lobulated neoplasm with fibrous septa. Polygonal epithelial cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli were among lymphocytes. Perivascular spaces were also found. This was diagnosed as B2 thymoma, following the WHO 2015 classification (2).

Surveillance CT chest performed 1 year later showed some lymph node enlargements. R4 lymph node biopsy was done by mediastinoscopy with histological diagnosis of non- keratinizing squamous thymic carcinoma infiltrating fibrous tissue. PDL1 evaluation was positive (tumor proportion score >10%). The patient was started on chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin, as well as concomitant mediastinal radiotherapy. Nine months later, the patient developed pain on the lateral aspect of her thigh. A new chest CT scan showed a lytic L3 involvement at the level of the left supra acetabular area and suspicion of involvement of the right greater trochanter. A more comprehensive assessment with MRI and bone scintigraphy revealed that these were metastatic lesions of thymic carcinoma. The patient started radiotherapy.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Discussion

The CMPT is a rare entity, the diagnosis is histological, and the presence of basal cells is required for the diagnosis. Kamata et al. have described the clinicopathological characteristics in ten cases: half had a history of smoking, all the lesions were small, peripheral, solid, or partially solid, of irregular contour, and the average size was 1 cm. All, except one patient, were asymptomatic, and the irregular appearance of the nodular contour suggested the possibility of adenocarcinoma in all cases (2,6). An association between CMPT and epithelial tumors of the thymus has not been described. In the presented case it seems a finding of two independent lesions. The published cases, like the patient presented, have been in older adults except for a CMPT in a 19-year-old adolescent (7), therefore, it should be considered as a differential diagnosis in a wider age range.

Onishi et al., in a retrospective study on 16 patients whose median age was 70 years, described the tomographic characteristics of CMPT. In most cases the lower lobes were affected, they were peripheral, solid nodules, close to the visceral pleura and with an average size of 9.1 mm. The same author compared the mucin content with the tomographic pattern and the expression of FDG in the PET SCAN. Most of the nodules with a pure or subsolid ground-glass opacity (GGO) pattern contained a high percentage of mucin, unlike the solid nodules (8) and it can be inferred that those CMPTs with a high mucinous component may present as subsolid lesions, while when the cellular component is predominant, they are expressed as solid tumors. It was not possible to establish any relationship between the level of FDG uptake and mucin content: of the 14 patients with low uptake, with SUV values of 0.51 to 1.35, 12 had a high mucin content, and the remaining two had a higher cellular component. The only case with moderate uptake and SUV value of 3.67 presented <30% mucin. The authors concluded that it is not possible to establish a clear relationship between the amount of mucin and the expression of FDG. As early-stage adenocarcinomas, CMPT have radiologic similarities, it is important that radiologists bear in mind this possible differential diagnosis (9).

The diagnosis of CMPT is morphological with the finding of a papillary proliferation in the lung parenchyma with mucinous, ciliated, and basal cells and accumulation of intra-alveolar mucin unrelated to the bronchiolar lumen. The proportion of cellular components is variable except for the basal cells that are required to make the diagnosis. These can be highlighted with immunohistochemistry (expression of cytokeratins 5/6 and p63/p40), but they are not necessary to make the diagnosis. Classic and non-classical CMPT terminology was proposed to describe these histological variants. Recently, the morphology, immunohistochemistry, and genetic analysis of a series of 25 cases were reviewed and the concept of Bronchiolar Adenomas was proposed, including the classic CMPT with or without papillae, considering them of the proximal bronchiolar type. Another subgroup, with almost no mucin or cilia, would be of the distal bronchiolar type. However, there are intermediate patterns, which leads to interpreting the group of bronchial adenomas as a morphological spectrum from the proximal to the distal type with occasional overlaps (4).

It is important for the pathologist to be familiar with this entity to provide an accurate diagnosis given its clinical importance. Intraoperative frozen sections might be challenging not only because it is a rare lesion, but also because ciliated cells are difficult to identify in frozen sections and in cytology smears. In our case, the intraoperative FNA showed mucin-producing cells in the smear that, based on the location of the lesion, were diagnosed as neoplastic cells. Still in permanent slides, because of the focal stromal destruction and complex architecture, these lesions may be confused with adenocarcinomas. However there two key features to consider in the diagnosis of CMPTs: the basal cell layer and the cilia, both of which were found in our patient’s specimen together with the papillary architecture (10). The importance in the differential diagnosis lies in the fact that none of the published CMPT had recurrences or metastases with a benign clinical behavior. But given their histological characteristics that sometimes present fibrosis that distorts the architecture, focal proliferation along alveolar septa, absence of capsule (although always circumscribed) and micropapillae, it seems more appropriate to consider them as tumors with low malignant potential (11).

An alert is a recently reported case with invasion by isolated less differentiated cells in a fibrosis focus that was interpreted as a possible malignancy from the basal cells (12).

The presence of driver mutations in BRAF, EGFR, and KRAS genes suggest that these lesions are neoplasms and not metaplastic, as could be interpreted morphologically. The most frequently found is p.V600E in exon 15 of BRAF. The alteration in EGFR (deletion in exon 19 E746-T751/S752V) is unusual in lung adenocarcinomas (13).

The treatment of CMPT is surgery. Lobectomy can be avoided due to the low degree of malignancy described in most of the reported cases. However, the impossibility of ruling out malignancy in the intraoperative period makes it necessary to practice lobectomy, the treatment of choice for lung cancer (14).

According current evidence none of the CMPT cases had recurrences or metastasis, thereby an appropriate differential diagnosis is critical for the adequate management of patients (2). It is important to underline that the CT and PET characteristic of the peripheral nodule of this case and a concomitant mediastinal mass led us to think about a diagnosis of lung carcinoma with mediastinal lymph node metastases. These findings and the misinterpreted intraoperative FNA determined the lobectomy.

Its association with a B2 thymoma is not published previously. No relationship between CMPT and epithelial tumors of the thymus has been described. The only known association with CMPT was in a female patient with symptoms of rheumatic polymyalgia, that disappeared right after tumor removal, considered then a paraneoplastic syndrome (15). No genetic similarities have been described between CMPT, thymomas and thymic carcinomas. In our case, both lesions appeared to be independent. Development of a non-keratinizing squamous thymus carcinoma from thymoma it is extraordinary but although rare, thymic neoplasms combined may occur.

Conclusions

It is mandatory to include CMPT in the differential diagnoses of peripheral lung nodules given the characteristics they share with lung cancers. The coexistence of a thymoma and a CMPT in the same patient is rare and even more unusual is the development of a metastatic thymic carcinoma. Further studies should be made to elucidate the possible biologic relationship between these lesions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med-20-60

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med-20-60

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med-20-60). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ishikawa Y. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor of the peripheral lung: benign or malignant? Pathol Clin Med (Byouri-to-Rinsho) 2002;20:964-5.

- Kamata T, Yoshida A, Kosuge T, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumors of the lung: a clinicopathologic analysis of 10 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:753-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, et al. editors. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press, 2015.

- Chang JC, Montecalvo J, Borsu L, et al. Bronchiolar adenoma: expansion of the concept of ciliated muconodular papillary tumors with proposal for revised terminology based on morphologic, immunophenotypic, and genomic analysis of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42:1010-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shao K, Wang Y, Xue Q, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of ciliated muconodular papillary tumor. J Cardiothorac Surg 2019;14:143. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen L, Lin J, Ren Z, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor of the lung: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Surg Case Rep 2019;2019:rjz247 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lau KW, Aubry MC, Tan GS, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor: a solitary peripheral lung nodule in a teenage girl. Hum Pathol 2016;49:22-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onishi Y, Kusumoto M, Motoi N, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor of the lung: thin-section CT findings of 16 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020;214:761-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onishi Y, Ito K, Motoi N, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor of the lung: 18F-FDG PET/CT findings of 15 cases. Ann Nucl Med 2020;34:448-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mikubo M, Maruyama R, Kakinuma H, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumors of the lung: cytologic features and diagnostic pitfalls in intraoperative examinations. Diagn Cytopathol 2019;47:716-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka S, Kondo R, Ishii K. Differential diagnosis of a rare papillary tumor and mucinous adenocarcinoma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2017;25:391-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyai K, Takeo H, Nakayama T, et al. Invasive form of ciliated muconodular papillary tumor of the lung: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Int 2018;68:530-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng Q, Luo R, Jin Y, et al. So-called "non-classic" ciliated muconodular papillary tumors: a comprehensive comparison of the clinicopathological and molecular features with classic ciliated muconodular papillary tumors. Hum Pathol 2018;82:193-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa M, Sumitomo S, Imamura N, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor of the lung: report of five cases. J Surg Case Rep 2016;2016:rjw144 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uchida T, Matsubara H, Ohnuki Y, et al. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor of the lung presenting with polymyalgia rheumatica-like symptoms: a case report. AME Case Rep 2019;3:37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Patané AK, Poleri C, Martín C. Ciliated muconodular papillary tumor and thymoma: unusual presentation for two types of rare tumors: a case report. Mediastinum 2021;5:18.