Deciphering the biology of thymic epithelial tumors

Introduction

Thymic epithelial tumors (TETs) are comprised of a family of anterior mediastinal malignancies that include thymomas, thymic carcinomas and thymic neuroendocrine cancers (1). There is considerable variation in the molecular characteristics and clinical behavior of TETs. All TETs have the capacity to metastasize widely and limit survival. Due to underlying immune deficits and persistence of autoreactive T-cells, patients with thymoma are at high risk for developing paraneoplastic autoimmune disorders (2). T-cell dysfunction also predisposes TET patients towards developing opportunistic infections and second cancers (3,4).

Histological classification of TETs is based on the World Health Organization (WHO) system, which categorizes tumors based on characteristics of the malignant epithelial cell and the degree of thymocyte infiltration (5). Staging of thymic cancers has historically been based on a surgical system developed by Masaoka and colleagues (6). However, a newly developed TNM classification is gradually replacing the Masaoka system for staging TETs (7). Early studies of genomic changes in TETs focused on a limited number of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, chromosomal copy number alterations and messenger RNA (mRNA) expression profiling (8,9).

The gold standard for treatment of TETs is surgical resection and it is often the only treatment modality required for patients with early-stage disease (10). Locally-advanced TETs require multimodality treatment that includes chemotherapy and radiation therapy in addition to surgery. Patients with unresectable or metastatic disease are treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (10). Few treatment options are available for relapsed or platinum-refractory TETs. Single-agent chemotherapy is associated with modest clinical activity and limited survival. An expansion of knowledge of the biology of thymic tumors has resulted in the emergence of a limited number of targeted biologic therapies and immunotherapy (11-13).

In this paper we review the molecular characteristics of TETs with a focus on the genomic, proteomic and microRNA (miRNA) profiles of these tumors. We also describe the role of the thymus in T-cell development and the immune deficits observed in TET patients. Clinical ramifications of recent insights into TET biology are outlined briefly.

Genomic landscape of TETs

Early studies to evaluate genomic aberrations in TETs analyzed tumor samples from patients with different stages of disease and various histological subgroups using a single or limited number of molecular platforms (9,14). The overall frequency of genomic alternations was low in TETs, with a relatively higher frequency observed in clinically aggressive WHO subtype B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas (14).

More recently, comprehensive genomic analyses of TETs have been conducted using multiple molecular platforms. The Cancer Genome Atlas network (TCGA) analyzed 117 TET samples (107 thymomas, 10 thymic carcinomas) derived from previously untreated patients, most of whom had early-stage disease and used the following platforms: somatic copy number variations, mRNA, miRNA, DNA methylation, and reverse phase protein array (15). TETs were found to have the lowest average tumor mutation burden among adult cancers. Recurrent somatic mutations were observed in general transcription factor IIi (GTF2I), HRAS, NRAS and TP53. Integrated analyses identified four distinct molecular subtypes of TETs that showed clinicopathologic similarities to WHO subtypes B, thymic carcinoma, type AB and a mix of type A and AB (15). Mutations in the GTF2I oncogene were found predominantly in type A and AB thymoma, which is consistent with previously published data (16). A higher prevalence of aneuploidy was observed in samples derived from patients with thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis (15).

An independent effort at developing a molecular classification of TETs was conducted by Lee and colleagues by using information on DNA mutations, mRNA expression and somatic copy number alterations from the TCGA data set (17). Two independent cohorts from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus were used for validation of results. Four molecular subgroups were identified with the following molecular characteristics: tumors with GTF2I mutations, GTF2I-wild type tumors with expression of genes associated with T-cell signaling, and tumors with chromosomal stability and instability. These molecular subgroups corresponded with WHO subtypes A or AB, B1 or B2, B2, and B2, B3 or C, respectively.

Genomic profile in pre-treated patients with advanced-stage disease

In contrast to TCGA analysis, which was conducted on tumor tissue obtained from patients without exposure to chemotherapy, Wang and colleagues sequenced 197 cancer-associated genes in tumors derived from 78 patients (31 thymomas, 47 thymic carcinomas) with advanced-stage TETs who had received chemotherapy previously (18). Somatic mutations were detected in 39 genes in 29 (62%) thymic carcinomas and 4 (13%) thymomas. Recurrent mutations were observed in 15 genes including BAP1, BRCA2, CDKN2A, CYLD, DNMT3A, HRAS, KIT, SETD2, SMARCA4, TET2, and TP53. Nine (23%) of 39 mutated genes are known to encode for epigenetic regulatory proteins that are responsible for chromatin remodeling, histone modification, and DNA methylation. Recurrent mutations in 7 of 9 epigenetic regulatory genes, including BAP1, ASXL1, SETD2, SMARCA4, DNMT3A, TET2, and WT1, were detected in 16 (34%) cases of thymic carcinoma but were absent in thymoma samples.

Proteome profile of TETs

Ongoing attempts to define the TET proteome are focused on identifying biomarkers to distinguish between histological subtypes of the disease. Characterization of the TET proteome also has the potential to offer insights into pathogenesis and identify targets for biologic therapy. Wang and colleagues conducted one of the first studies to characterize the proteome of all subtypes of thymoma (19). Thirty-six tumor samples representing WHO subtypes A, AB, B1, B2 and B3 thymoma were evaluated by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and compared with normal thymic tissue. Sixty-one proteins were found to be differentially expressed in neoplastic tissue compared with normal thymus and formed two distinct clusters consisting of thymoma subtypes AB, B1 and B2 versus subtypes A and B3. Seven of 61 proteins belonged to collagen family and were downregulated in thymomas. Dysregulation of collagen metabolism in the tumor microenvironment has been previously shown to have variable effects on tumor growth at various stages of cancer development (20). The oncoprotein, stathmin, was found to be upregulated in thymoma subtypes AB, B1 and B2. Stathmin is associated with microtubule biology and is shown to be associated with high cell proliferation, poor prognosis and resistance to microtubule-targeting drugs such as taxanes, which are used for systemic therapy of TETs (21,22). Desmoyokin, encoded by the AHNAK (neuroblast differentiation-associated) gene was significantly downregulated in type B thymomas but exhibited no significant differences in expression in subtypes A and AB when compared with normal thymic tissue. Hence, desmoyokin could serve as a marker to differentiate between various subtypes of thymoma. Ninety proteins were found to be differentially expressed between type A and type B3 thymoma. Biological processes associated with these proteins include apoptosis inhibition and cell cycle progression.

Proteogenomic heterogeneity in thymic carcinoma

Mutational evolution and heterogeneity at metastatic sites have been characterized for various tumor types but scant data are available in the context of TETs (23,24). As part of a rapid autopsy protocol for thoracic malignancies, our group has evaluated genomic and proteomic heterogeneity between metastases from seven distinct anatomic sites in a patient with metastatic squamous cell thymic carcinoma (25). An average of 14 non-truncal driver mutations were detected and extreme mutational heterogeneity was observed between metastatic sites. The cytosine deaminase activity of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) correlated strongly with mutational heterogeneity. Transcriptomic and proteomic heterogeneity in immune signatures resulted in variations in the immune microenvironment at metastatic sites. These observations provide an explanation for variations in the degree of response to systemic therapy at different sites of disease in an individual patient and merit further evaluation.

miRNA profile of TETs

miRNAs are double-stranded, non-protein-coding RNAs involved in post-transcriptional gene expression (26). These small RNAs play important roles in thymic development and involution (27). The role of miRNAs as oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes is increasingly coming into focus and aberrant miRNA expression is present in various cancers (28,29). miRNA expression profiling of TETs has the potential to yield information on tumorigenesis, help differentiate between histologic subtypes of these tumors and uncover potential therapeutic targets.

A study of 54 TET samples derived from surgical resections in patients not exposed to chemotherapy or radiation therapy revealed differential expression of 87 miRNAs compared with normal thymic tissue (30). Differences in miRNA expression were also observed between thymoma and thymic carcinoma and between subtypes of thymoma. Amongst the most significant changes was upregulation of miR-21-5p, which promotes cell proliferation, and downregulation of miR-145-5p, which functions as a tumor suppressor (31,32).

Radovich and colleagues analyzed 13 TET samples and found overexpression of a large miRNA cluster on chromosome 19q13.42 (C19MC) in type A and AB thymomas resulting in activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway (33). In contrast, C19MC expression was absent in type B thymomas. These results provide a rationale for evaluating PI3K pathway inhibitors in TETs.

Enkner and colleagues also observed overexpression of C19MC in type A thymomas and absence of expression in thymic carcinomas (34). In addition, they found differential expression of a miRNA cluster on chromosome 14q32 (C14MC) between the two histologies with significant down regulation in thymic carcinomas. C14MC appears to have tumor suppressor properties in gastrointestinal stromal tumor and glioma (35,36). Hence, it is conceivable that downregulation of C14MC can contribute to the pathogenesis of thymic carcinoma.

Among non-clustered miRNA, miR21, miR-9-3 and miR-375 are strongly expressed in thymic carcinoma with low expression in type A thymoma whereas, miR-34b, miR-34c, miR-130a, and miR-195 are overexpressed in type A thymoma but infrequently expressed in thymic carcinoma (34). Potential biologic functions of these miRNAs include tumors suppression (miR-34b, miR-34c, miR-130a, and miR-195), oncogenesis (miR21), and immune evasion (miRNA-34), all of which might contribute to the tumorigenicity of thymic carcinoma (34,37-39).

Evaluation of circulating miRNAs can be developed as a non-invasive tool to evaluate the effect of treatment. In a small study of 5 patients with early-stage, type B thymoma undergoing surgical resection, miR-21-5p and miR-148a-3p levels were found to be elevated in plasma at baseline and showed a significant reduction in the post-operative period (40). If validated in larger studies, these results demonstrate the potential utility of using circulating miRNAs as prognostic biomarkers in patients with TETs.

Immunobiology of TETs

Role of the thymus in T-cell development

Through a series of complex steps, the thymus gland plays a crucial role in the development of central T-cell tolerance, which is required to prevent the emergence of autoimmune diseases (41,42). This process is influenced by the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene and the transcription factor forebrain-expressed zinc finger 2 (Fezf2), which promote the expression of tissue-specific antigens to developing T-cells in the thymic medulla resulting in the deletion of self-reactive T-cells by negative selection (42-44). Since the process of negative selection occurs in the thymic medulla, thymic architecture has an impact on maturation of thymocytes. AIRE also promotes the development of a population of self-reactive, immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) by positive selection, which hinder the development of autoimmune disease (45,46).

Thymomas and paraneoplastic autoimmune disorders

Changes in thymic architecture and deficient expression of AIRE and major histocompatibility (MHC) class II in thymoma results in a breakdown of central immune tolerance and a predisposition towards autoimmunity. A wide spectrum of autoimmune disorders has been described in association with thymoma (2). Myasthenia gravis is the most common paraneoplastic disorder and is observed most often in patients with WHO subtype B tumors. Thymomas with associated myasthenia gravis have a higher prevalence of aneuploidy and neoplastic thymic epithelial cells overexpress antigens that share sequence similarities with autoimmune targets (15). These findings suggest that defective immune tolerance is unlikely to be the only mechanism underlying the emergence of paraneoplastic autoimmunity.

Thymomas and immunodeficiency

Immune defects associated with thymoma have implications beyond the predisposition towards development of autoimmune disorders. Hypogammaglobulinemia and acquired T-cell immunodeficiency can increase the risk for development of opportunistic infections (47). An increase in secondary malignancies is also observed in TET patients, possibly because of defective immune surveillance (48).

Good’s syndrome consists of defects in humoral and cellular immunity and is seen in approximately 5% of patients with thymoma (49,50). The classical immunological deficit associated with Good’s syndrome is hypogammaglobulinemia. It is accompanied by B-cell lymphopenia, CD4 cell lymphopenia and impaired T-cell activation (51). Acquired immunodeficiency frequently coexists with autoimmunity in thymoma patients and increases susceptibility to opportunistic infections (47,52).

T-cell abnormalities can occur in thymoma patients even in the absence of Good’s syndrome. Changes include an increase in the number of circulating naïve T-cells and a reduction in Treg numbers, which can be accompanied by functional impairment of Tregs and impaired mitogen responses (51,53-55).

The pathogenesis of immunodeficiency in thymoma is poorly understood. An acquired defect in CD247 in naïve T-cells has been described in patients with lymphocyte-rich thymomas, which causes T-cell receptor hyporesponsiveness and cutaneous anergy (56). B-cell lymphopenia in Good’s syndrome is postulated to be caused by elimination of B-cells in the bone marrow by autoreactive CD8 T cells and T-cell mediated suppression of B-cell growth (57,58). Defects in cellular immunity in thymoma patients are also caused by anti-cytokine antibodies targeting interferons, interleukin-17 (IL-17) and IL-22 (43,59,60). Acquired immunodeficiency caused by anti-cytokine antibodies can increase the risk for development of opportunistic infections (43,61,62).

Clinical implications of TET biology

Impact of TET genomic profile on drug development

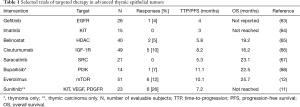

A low tumor mutation burden coupled with a low frequency of actionable mutations presents obstacles for the development of targeted biologic therapies for TETs. Apart from a few exceptions such as sunitinib and everolimus, clinical trials of targeted therapies have yielded disappointing results in patients with advanced TETs (Table 1). This has resulted in the search for new targets to facilitate drug development. Mesothelin and exportin1 (XPO1) are examples of biologic targets expressed in TETs that can be utilized for development of tumor-directed therapy (69,70).

Full table

Mesothelin is a cell surface glycoprotein with high levels of expression in most thymic carcinomas (71). Several drugs are in development to target mesothelin including anetumab, an antibody-drug conjugate that is undergoing evaluation in patients with advanced thymic carcinoma (NCT03102320) (69).

XPO1 is involved in nuclear export of tumor suppressor proteins, including p53 and inhibition of XPO1 in TET cells has been shown to induce anti-tumor activity in vitro (70). Selinexor, a small-molecule inhibitor of XPO1, is under evaluation in a phase II trial in patients with advanced TETs (NCT03193437).

Effect of genomic profile on survival and disease recurrence

Certain genomic characteristics of TETs appear to be of prognostic value. In a study of genetic alterations in patients with advanced TETs, the presence of somatic mutations was associated with shorter survival (median survival 59 versus 142 months; P<0.05) (18). Mutations in p53 were also associated with worse overall survival (OS) compared with p53-wild-type tumors (median survival 19 versus 106 months; P=0.0003) (18). A negative impact of p53 mutations on survival was also detected in 123 TET cases derived from the TCGA database. Median survival in patients with p53-mutated tumors was 25.4 months. Presence of a p53 mutation was also associated with a shorter time to disease relapse (median disease-free survival was 9.7 months versus not evaluable in p53-wild-type cases due to a low frequency of relapse) (72).

Presence of a GTF2I mutation and enrichment of genes involved in T-cell signaling are associated with favorable disease-free survival and OS in contrast to tumors with chromosomal instability (17).

Other prognostic markers under investigation include expression of the genes SOX2 and CA9, which are reported to be associated with shorter survival in TET patients and the methylation status of the genes KSR1, ELF3, ILRN and RAG1, which have variable effects on OS (73-75).

Defective immune tolerance and risk of immunotherapy

Defects in central immune tolerance and persistence of autoreactive T-cells in patients with thymoma places them at high risk for developing toxicity related to immune activation resulting from immunotherapy. Unsurprisingly, an increased frequency of immune-related adverse events has been observed in early trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors and cancer vaccines in TET patients despite exclusion of patients with a history of paraneoplastic autoimmune diseases (13,76-78). For immunotherapy to emerge as a safe and feasible alternative for TET patients, especially for those with advanced thymoma, it is imperative to develop strategies to identify patients at risk for immune-related toxicity and establish treatment protocols for adverse events that are observed in response to treatment.

Altered T-cell function and risk of infections and secondary malignancies

Immune dysfunction places TET patients at risk for development of opportunistic infections (3,47). Early recognition and treatment of infectious complications is important in reducing morbidity and improving quality of life. Opportunistic infections observed in patients with thymoma include mucocutaneous candidiasis, pneumocystis pneumonia, cytomegalovirus and herpes virus infections, cryptococcosis and non-tubercular mycobacterial infections (3,47). Patients with hypogammaglobulinemia and recurrent infections can potentially benefit from prophylactic administration of intravenous immunoglobulin.

TET patients are also at increased risk for developing extrathymic malignancies including non-melanoma skin cancers, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, thyroid cancer and lung cancer (4,79). Since second cancers can adversely affect survival, appropriate surveillance and management should be instituted per established guidelines.

Conclusions

The past decade has witnessed a rapid increase in the understanding of the biology of thymic cancers. This process has been facilitated by the availability of next-generation sequencing technologies, the ability to conduct multiplatform analyses and the establishment of thymoma and thymic carcinoma cell lines. Ongoing studies are uncovering novel biologic targets that can be harnessed to develop new systemic therapies. Greater insights into the immunobiology of TETs are resulting in improved management of autoimmune and immunodeficiency disorders and have the potential to mitigate the risks associated with immunotherapy. Efforts to address existing gaps in the knowledge of TET biology will hopefully translate into improved patient outcomes in the future.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors Mirella Marino and Brett W. Carter for the series “Dedicated to the 9th International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group Annual Meeting (ITMIG 2018)” published in Mediastinum. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med.2019.08.03). The series “Dedicated to the 9th International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group Annual Meeting (ITMIG 2018)” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kelly RJ, Petrini I, Rajan A, et al. Thymic malignancies: from clinical management to targeted therapies. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4820-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marx A, Willcox N, Leite MI, et al. Thymoma and paraneoplastic myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity 2010;43:413-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinez B, Browne SK. Good syndrome, bad problem. Front Oncol 2014;4:307. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Engels EA. Epidemiology of thymoma and associated malignancies. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:S260-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke A, et al. editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. World Health Organization. 2015.

- Masaoka A, Monden Y, Nakahara K, et al. Follow-up study of thymomas with special reference to their clinical stages. Cancer 1981;48:2485-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Detterbeck FC, Stratton K, Giroux D, et al. The IASLC/ITMIG Thymic Epithelial Tumors Staging Project: proposal for an evidence-based stage classification system for the forthcoming (8th) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:S65-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhn E, Wistuba II. Molecular pathology of thymic epithelial neoplasms. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2008;22:443-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Girard N, Shen R, Guo T, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis reveals clinically relevant molecular distinctions between thymic carcinomas and thymomas. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:6790-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Girard N, Ruffini E, Marx A, et al. Thymic epithelial tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2015;26:v40-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas A, Rajan A, Berman A, et al. Sunitinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory thymoma and thymic carcinoma: an open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:177-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zucali PA, De Pas T, Palmieri G, et al. Phase II Study of Everolimus in Patients With Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma Previously Treated With Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:342-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giaccone G, Kim C, Thompson J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with thymic carcinoma: a single-arm, single-centre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:347-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajan A, Girard N, Marx A. State of the art of genetic alterations in thymic epithelial tumors. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:S131-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Radovich M, Pickering CR, Felau I, et al. The Integrated Genomic Landscape of Thymic Epithelial Tumors. Cancer Cell 2018;33:244-58. e10.

- Petrini I, Meltzer PS, Kim IK, et al. A specific missense mutation in GTF2I occurs at high frequency in thymic epithelial tumors. Nat Genet 2014;46:844-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HS, Jang HJ, Shah R, et al. Genomic Analysis of Thymic Epithelial Tumors Identifies Novel Subtypes Associated with Distinct Clinical Features. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4855-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Thomas A, Lau C, et al. Mutations of epigenetic regulatory genes are common in thymic carcinomas. Sci Rep 2014;4:7336. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Branson OE, Shilo K, et al. Proteomic Signatures of Thymomas. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166494 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fang M, Yuan J, Peng C, et al. Collagen as a double-edged sword in tumor progression. Tumour Biol 2014;35:2871-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hassan MK, Watari H, Mitamura T, et al. P18/Stathmin1 is regulated by miR-31 in ovarian cancer in response to taxane. Oncoscience 2015;2:294-308. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nemunaitis J. Stathmin 1: a protein with many tasks. New biomarker and potential target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2012;16:631-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar A, Coleman I, Morrissey C, et al. Substantial interindividual and limited intraindividual genomic diversity among tumors from men with metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Med 2016;22:369-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, et al. Tracking the Evolution of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2109-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roper N, Gao S, Maity TK, et al. APOBEC Mutagenesis and Copy-Number Alterations Are Drivers of Proteogenomic Tumor Evolution and Heterogeneity in Metastatic Thoracic Tumors. Cell Rep 2019;26:2651-66.e6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004;116:281-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu M, Gan T, Ning H, et al. MicroRNA Functions in Thymic Biology: Thymic Development and Involution. Front Immunol 2018;9:2063. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kent OA, Mendell JT. A small piece in the cancer puzzle: microRNAs as tumor suppressors and oncogenes. Oncogene 2006;25:6188-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 2005;435:834-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ganci F, Vico C, Korita E, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of thymic epithelial tumors. Lung Cancer 2014;85:197-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meng F, Henson R, Wehbe-Janek H, et al. MicroRNA-21 regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer. Gastroenterology 2007;133:647-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cioce M, Ganci F, Canu V, et al. Protumorigenic effects of mir-145 loss in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Oncogene 2014;33:5319-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Radovich M, Solzak JP, Hancock BA, et al. A large microRNA cluster on chromosome 19 is a transcriptional hallmark of WHO type A and AB thymomas. Br J Cancer 2016;114:477-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Enkner F, Pichlhofer B, Zaharie AT, et al. Molecular Profiling of Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma: Genetic Differences and Potential Novel Therapeutic Targets. Pathol Oncol Res 2017;23:551-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haller F, von Heydebreck A, Zhang JD, et al. Localization- and mutation-dependent microRNA (miRNA) expression signatures in gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs), with a cluster of co-expressed miRNAs located at 14q32.31. J Pathol 2010;220:71-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lavon I, Zrihan D, Granit A, et al. Gliomas display a microRNA expression profile reminiscent of neural precursor cells. Neuro Oncol 2010;12:422-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu L, Chen L, Xu Y, et al. microRNA-195 promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenicity of human colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;400:236-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen L, Wan Z, Ma Y, et al. The clinical utility of microRNA-21 as novel biomarker for diagnosing human cancers. Tumour Biol 2015;36:1993-2005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cortez MA, Ivan C, Valdecanas D, et al. PDL1 Regulation by p53 via miR-34. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bellissimo T, Russo E, Ganci F, et al. Circulating miR-21-5p and miR-148a-3p as emerging non-invasive biomarkers in thymic epithelial tumors. Cancer Biol Ther 2016;17:79-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maverakis E, Goodarzi H, Wehrli LN, et al. The etiology of paraneoplastic autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2012;42:135-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng M, Anderson MS. Thymic tolerance as a key brake on autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 2018;19:659-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kisand K, Lilic D, Casanova JL, et al. Mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmunity against cytokines in APECED and thymoma patients: clinical and pathogenetic implications. Eur J Immunol 2011;41:1517-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perniola R. Twenty Years of AIRE. Front Immunol 2018;9:98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malchow S, Leventhal DS, Nishi S, et al. Aire-dependent thymic development of tumor-associated regulatory T cells. Science 2013;339:1219-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perry JSA, Lio CJ, Kau AL, et al. Distinct contributions of Aire and antigen-presenting-cell subsets to the generation of self-tolerance in the thymus. Immunity 2014;41:414-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Multani A, Gomez CA, Montoya JG. Prevention of infectious diseases in patients with Good syndrome. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018;31:267-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Granato F, Ambrosio MR, Spina D, et al. Patients with thymomas have an increased risk of developing additional malignancies: lack of immunological surveillance? Histopathology 2012;60:437-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelleher P, Misbah SA. What is Good's syndrome? Immunological abnormalities in patients with thymoma. J Clin Pathol 2003;56:12-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malphettes M, Gerard L, Galicier L, et al. Good syndrome: an adult-onset immunodeficiency remarkable for its high incidence of invasive infections and autoimmune complications. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:e13-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos P, Fisch P. Acquired T-Cell Immunodeficiency in Thymoma Patients. Crit Rev Immunol 2016;36:315-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelesidis T, Yang O. Good's syndrome remains a mystery after 55 years: A systematic review of the scientific evidence. Clin Immunol 2010;135:347-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoffacker V, Schultz A, Tiesinga JJ, et al. Thymomas alter the T-cell subset composition in the blood: a potential mechanism for thymoma-associated autoimmune disease. Blood 2000;96:3872-9. [PubMed]

- Ströbel P, Rosenwald A, Beyersdorf N, et al. Selective loss of regulatory T cells in thymomas. Ann Neurol 2004;56:901-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thiruppathi M, Rowin J, Li Jiang Q, et al. Functional defect in regulatory T cells in myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1274:68-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos P, Dopfer EP, Malkovsky M, et al. A novel thymoma-associated immunodeficiency with increased naive T cells and reduced CD247 expression. J Immunol 2015;194:3045-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masci AM, Palmieri G, Vitiello L, et al. Clonal expansion of CD8+ BV8 T lymphocytes in bone marrow characterizes thymoma-associated B lymphopenia. Blood 2003;101:3106-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayward AR, Paolucci P, Webster AD, et al. Pre-B cell suppression by thymoma patient lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol 1982;48:437-42. [PubMed]

- Burbelo PD, Browne SK, Sampaio EP, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies are associated with opportunistic infection in patients with thymic neoplasia. Blood 2010;116:4848-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meager A, Wadhwa M, Dilger P, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies in autoimmunity: preponderance of neutralizing autoantibodies against interferon-alpha, interferon-omega and interleukin-12 in patients with thymoma and/or myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol 2003;132:128-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barcenas-Morales G, Cortes-Acevedo P, Doffinger R. Anticytokine autoantibodies leading to infection: early recognition, diagnosis and treatment options. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2019;32:330-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Browne SK. Anticytokine autoantibody-associated immunodeficiency. Annu Rev Immunol 2014;32:635-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurup A, Burns M, Dropcho S, et al. Phase II study of gefitinib treatment in advanced thymic malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7068. [Crossref]

- Palmieri G, Marino M, Buonerba C, et al. Imatinib mesylate in thymic epithelial malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:309-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giaccone G, Rajan A, Berman A, et al. Phase II study of belinostat in patients with recurrent or refractory advanced thymic epithelial tumors. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2052-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajan A, Carter CA, Berman A, et al. Cixutumumab for patients with recurrent or refractory advanced thymic epithelial tumours: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:191-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gubens MA, Burns M, Perkins SM, et al. A phase II study of saracatinib (AZD0530), a Src inhibitor, administered orally daily to patients with advanced thymic malignancies. Lung Cancer 2015;89:57-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu Zaid MI, Radovich M, Althouse SK, et al. A phase II study of BKM120 (buparlisib) in relapsed or refractory thymomas. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:e20580 [Crossref]

- Hassan R, Thomas A, Alewine C, et al. Mesothelin Immunotherapy for Cancer: Ready for Prime Time? J Clin Oncol 2016;34:4171-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conforti F, Zhang X, Rao G, et al. Therapeutic Effects of XPO1 Inhibition in Thymic Epithelial Tumors. Cancer Res 2017;77:5614-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas A, Chen Y, Berman A, et al. Expression of mesothelin in thymic carcinoma and its potential therapeutic significance. Lung Cancer 2016;101:104-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li VD, Li KH, Li JT. TP53 mutations as potential prognostic markers for specific cancers: analysis of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and the International Agency for Research on Cancer TP53 Database. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019;145:625-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee GJ, Lee H, Woo IS, et al. High expression level of SOX2 is significantly associated with shorter survival in patients with thymic epithelial tumors. Lung Cancer 2019;132:9-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohtaki Y, Shimizu K, Kawabata-Iwakawa R, et al. Carbonic anhydrase 9 expression is associated with poor prognosis, tumor proliferation, and radiosensitivity of thymic carcinomas. Oncotarget 2019;10:1306-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li S, Yuan Y, Xiao H, et al. Discovery and validation of DNA methylation markers for overall survival prognosis in patients with thymic epithelial tumors. Clin Epigenetics 2019;11:38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajan A, Heery CR, Perry S, et al. Safety and clinical activity of anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody (ab) avelumab (MSB0010718C) in advanced thymic epithelial tumors (TETs). J Clin Oncol 2016;34:e20106 [Crossref]

- Cho J, Kim HS, Ku BM, et al. Pembrolizumab for Patients With Refractory or Relapsed Thymic Epithelial Tumor: An Open-Label Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2162-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oji Y, Inoue M, Takeda Y, et al. WT1 peptide-based immunotherapy for advanced thymic epithelial malignancies. Int J Cancer 2018;142:2375-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamata T, Yoshida S, Wada H, et al. Extrathymic malignancies associated with thymoma: a forty-year experience at a single institution. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017;24:576-81. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Rajan A, Zhao C. Deciphering the biology of thymic epithelial tumors. Mediastinum 2019;3:36.